Teaching High School Students to Read Honestly

I hated math class in high school. On homework, I often gave up after one or two questions because the problems were “too hard.” With the rest, I copied over the problems and then wrote random numbers indiscriminately—but neatly—underneath. I gathered “my work” together into a pile of papers, stapled them, and turned them in. While I received some credit, I had learned nothing. And, I was completely unprepared for–and performed poorly on–my tests.

When I became an English teacher, I saw how my students tried to bluff me. They would skim the assigned text, finding words that matched those in my comprehension questions, and then claim that they had found “textual evidence.” I wondered how I could get them to engage with the text honestly. Then I discovered Riveting Results.

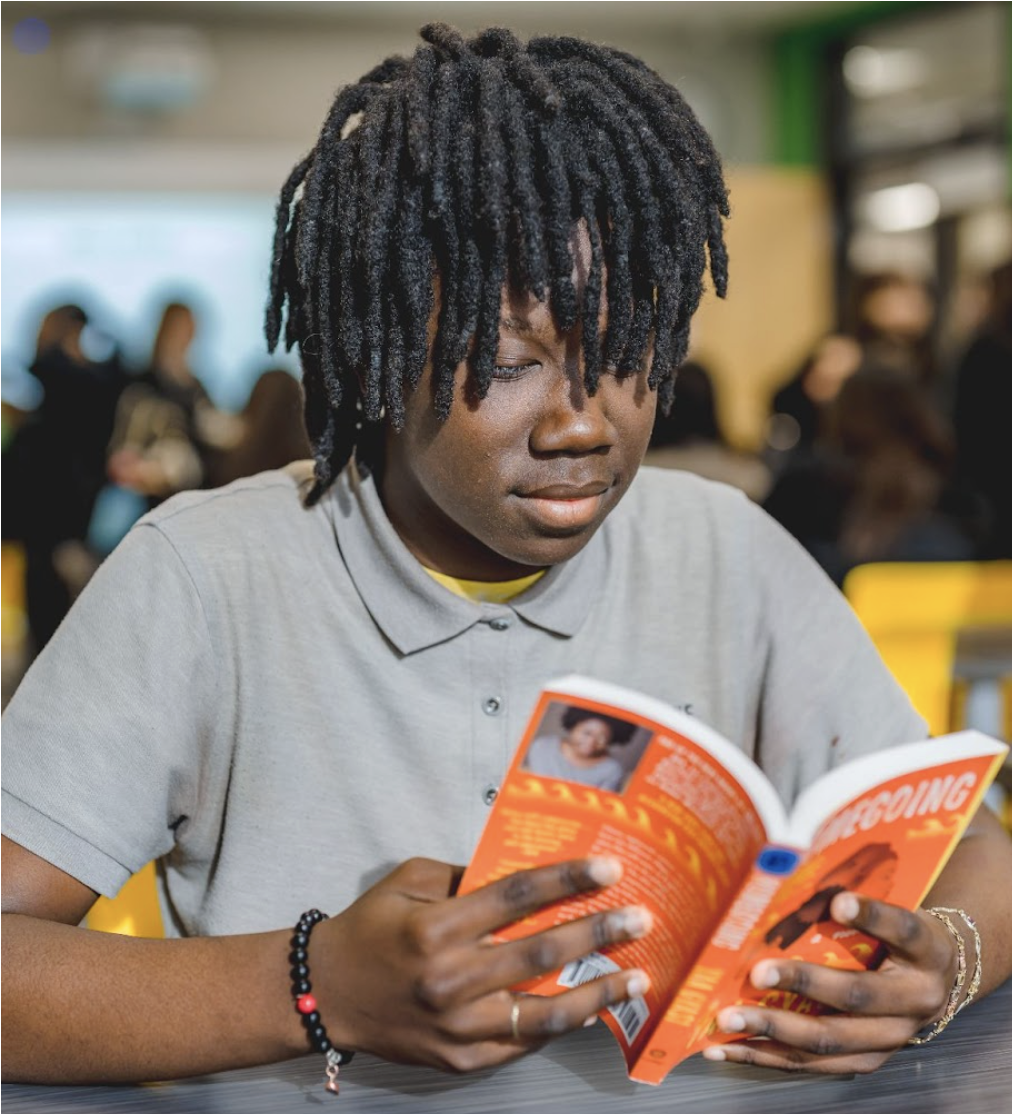

Riveting Results’ high school ELA program asks students to record themselves reading complex text aloud. One might think that reading aloud would make students more self-conscious, more eager to bluff. Yet, the Riveting Results Fluency activity has the exact opposite effect. Students learn how to read with increasingly precise and thoughtful expressiveness.

The program breaks advanced literature and nonfiction down into sections. As they read each section, students submit a recording in which they perform a particular fluency skill with a passage from the section. Early in the year, students practice reading just one sentence, receiving regular feedback from remote scorers. When students receive scores of “Masterful,” they progress to recording longer passages and employing new fluency skills.

Listen to the Fluency recording of a Riveting Results tenth grader named Hugo. In this recording of The Narrative of Frederick Douglass, Hugo chooses to convey the emotion of “confusion.” His recording is choppy and emphasizes phrases indiscriminately. His scorer gave him a “Not Yet” and wrote the following: “I couldn’t hear distinct confusion in your voice. Read the entire passage, but make 1-2 sentences stand out by sounding more confused than in any of the other sentences you read.” To submit a more expressive recording that receives a Masterful score, Hugo will need to practice.

Months later, after making over twenty additional fluency recordings, Hugo tackles a scene towards the end of Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing HERE. In this passage, the character Yaw expresses the disgust he feels with his own facial disfigurement by describing the nervous movements that his maid makes in his presence. Hugo’s scorer gives him a “Masterful” for the recording and provides written feedback that recognizes its impact. She wrote: “I didn't realize words could sound so sad. I'm stunned. The way you read the sentence really brought out the shame Yaw felt about his scar.” Early in this recording, you can hear Hugo struggling to read smoothly. As he proceeds, however, his choppiness disappears and he taps into Yaw’s embarrassment. He conveys the pain that ultimately moved his scorer.

Hugo’s practice routine and the type of feedback he received (“I'm stunned. The way you read the sentence really brought out the shame Yaw felt about his scar.”) not only improved his fluency but provided a bridge that drew him deeper and deeper into the text.

Bluffing was no longer an option.

To find out more about how Riveting Results can support your high school’s literacy vision, email contact@rr.tools.

We want to know what you think.

We recommend you read these next

Meet The Team

The Riveting Results program works because it incorporates feedback from dozens of educators experienced in the classroom and in running schools. Unlike other programs that primarily use academic experts to review materials, Riveting Results gets feedback from educators who have actually used Riveting Results in the classroom to develop students reading and writing performance.

contact us